by Bart van Klink

Image: Bart van Klink

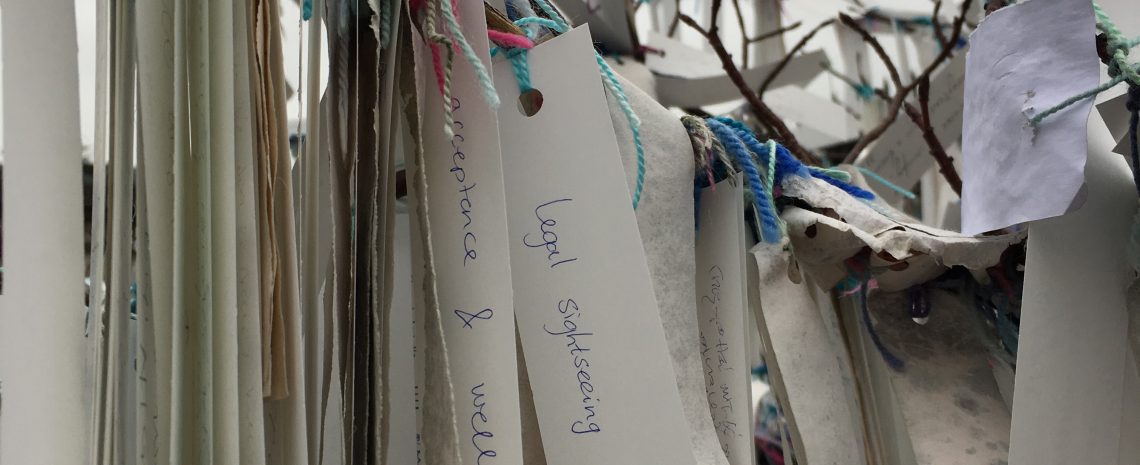

Rojava Parliament, Eindhoven

New World Summit is an artistic and political organisation, founded by the Dutch-Swiss artist Jonas Staal in 2012, in which artists, political actors and activists collaborate. It aims at establishing alternative parliaments for political organizations that, as a consequence of the ‘war on terror’, are stateless and blacklisted. It wants to offer people who have been excluded from the ‘current practice of democracy’ a platform to act and interact politically. These alternative parliaments are created by means of art, architecture and design, on the actual locations where the excluded groups live (for instance, in Mali or Syria) or somewhere else (in Berlin, Oslo, Utrecht, and so on), in theatres, art institutions and public spaces.

In an article entitled ‘Law of the State, Truth of Art’, Staal presents The New World Summit as a state of exception that challenges the current legal and political order: “Our state of exception (…) is the state of exception of art itself. Not a state in terms of a governmental structure, but a state in terms of an existential condition; and a space exceptional due to its very ambiguity in the domain of the law”. As Staal, argues “the New World Summit attempts to bring the law itself to trial as an instrument of state terror.”

As a case study, I will focus on the New World Summit in Rojava, a (more or less) autonomous region in North and East Syria. The Summit’s contribution to the Rojava revolution constitutes an interesting case since it challenges, by aesthetic means, current notions of political representation and democratic participation. Although it aspires to be more than utopian, its significance lies in my view primarily on a symbolic level, as it incites the social imagination to think of alternative ways of organizing and exerting power. In an earlier article, I argued that it is exactly its apparent impossibility that makes the project so valuable and inspiring for law and legal development. By erecting a parliament for Rojava, it presents a picture of what the legal and political order could or should look like when things were different. As such, it is an exercise in “utopian world-making”.

in what ways is art, vice versa, shaped by law and politics?

As next step, I want to explore what kind of relation the New World Summit in Rojava establishes between architecture on the one hand and law and politics on the other hand. In what sense can architecture be understood as a transformative power? What exactly does the ‘state of exception’ entail, which Staal intends to create in the current legal and political order? More fundamentally, how can art change law and politics and in what ways is art, vice versa, shaped by law and politics? According to Mouffe, critical art offers “counter-hegemonic interventions” which challenge the existing consensus. Similarly, Rancière claims that, if there is a connection between art and politics, it has to be understood in terms of dissensus. In his view, critical art aims to produce a new perception of the world and to create a commitment to its transformation. From this agonistic perspective, Staal’s project can be conceived as a “space of refuge for dissensual practise”. However, as Rancière argues, there never can be direct (causal) connection between law and politics and the aesthetic domain: “artworks can produce effects of dissensus precisely because they neither give lessons nor have any destination”. So what are these ‘effects of dissensus’ and how do they affect the legal and political order?

Bart van Klink is professor of legal methodology at VU Amsterdam. His expertise includes authority, resistance, populism, and legal change. He recently co-edited a volume titled Utopian Thinking in Law, Politics, Architecture and Technology: Hope in a Hopeless World (Elgar 2022).

This piece is part of the legal sightseeing

mini-blog series on institutional architecture:

view the whole series!