by Lucy Finchett-Maddock

Image: Nico Wikkerman

Huisje, Boompje, Beestje, 2007

Acrylic on canvas, 40 x 40 cm

Photo: Renske Vos

Outsider art is a complex term and genre in artistic practice that has changed and evolved over the years. It has historically been connected to art made by incarcerees of mental institutions, otherwise known as ‘psychotic art’ or art brut meaning ‘raw art’, a term coined by Jean Dubuffet in the 1950s. The phenomena has been linked with the development of art in therapy, inclusive art and arts-based rehabilitation, from the end of the nineteenth century. Now some artists self-refer as outsider artists to keep their work separate from the mainstream. Nevertheless, it remains a name given by the Western art world to distinguish it from predominantly fine art practice. It is very often those marginalised by race, gender, disability, disempowered economically and politically, who fall within the brackets of outsider artists.

Seeking to pinpoint materio-legislative junctures in the development of outsider art’s entanglement with psychiatric institutionalisation (such as assimilating the physical structures within which the patients were confined, with the aesthetic forms produced), with a particular interest in carceral architecture’s impact on the creation of outsider art, is the focus of this piece; and the law’s wider role in the construction of aesthetic forms.

In a series of legislative manoeuvres in England and Wales over a few hundred years (Madhouse Act of 1774, Lunacy Act 1980, Mental Deficiency Act 1913, Mental Health Act 1959, Hospital Plan 1962, and National Health and Community Care Act 1990), there came the rise and fall of the psychiatric institution, and prevalence of psychopharmacology and the process of decarceration thereinafter. It is the material architectures of institutionalisation that are of key concern for this research; given it is only since the Mental Health Act 1983 that those who had been committed to asylums had a right to appeal their certification.

Art historian Esther Leslie’s work on institutionalisation and aesthetic forms will be used as a theoretical backdrop, combined with speculative realist artist’s work on law and materiality, Amanda Beech. Institutions concerned will include psychiatric hospital museums of Bristol, Wakefield and Glasgow.

WIP Paper

The ‘cult of the artist as a visionary’ on the border of genius and insanity has been in Western cultural consciousness since the Enlightenment, found no more iconic than in the troubled temperament of Van Gogh and his severed ear, or the confusion, depression and anxiety experienced by the iconic Frida Kahlo. Despite these barriers, both are some of the most famous artists of the fine art world. Being ‘troubled’ has, however, often estranged some artists, those most definitively termed as ‘outsider’. Outsider art is a complex term and genre in artistic practice that has changed and evolved over the years. It has historically been connected to art made by incarcerees of mental institutions, otherwise known as ‘psychotic art’ or art brut meaning ‘raw art’, a term coined by Jean Dubuffet in the 1950s. This term was later extended to art that was made by those who had not had any form of training, or artists not concerned with selling their work, under the term ‘outsider art’ by Roger Cardinal in 1972 . The phenomena has been linked with the development of art in therapy, inclusive art and arts-based rehabilitation, from the end of nineteenth century.

Outsider art’s entanglement with psychiatric institutionalisation and the development of art therapy is of key interest, seeking to pinpoint legislative connections and important legal moments in the development of the genre that coincide with narratives of mental health management from the nineteenth century onwards. Michel Foucault’s Madness and Civilization (1961) famously propounded the invention of madness and the mass incarceration of undesirables as a method of rationalisation and efficiency, a narrative of labelling that may also be found within the role of mental health law and outsider art.

In a series of legislative manoeuvres over a few hundred years (Madhouse Act of 1774, Lunacy Act 1980, Mental Deficiency Act 1913, Mental Health Act 1959, Hospital Plan 1962, and National Health and Community Care Act 1990), there came the rise and fall of the psychiatric institution, and prevalence of psychopharmacology and the process of decarceration thereinafter. The psychotic art that was made within the institutional setting then adapted, where care in the community from the 1980s was argued to “substantially alter[..] the supply of Outsider Art from asylums, if not effectively clos[ing] it off.” Since then, art therapy has developed, connecting mental illness with creative forms, and the term outsider art has been extended beyond the mental institution. Now some artists self-refer as outsider artists to keep their work separate from the mainstream. Nevertheless, it remains a name given by the Western art world to distinguish it from predominantly fine art practice. A large proportion of outsider artwork is still created by those who may not understand themselves as artists, let alone outsider artists, such as work created by people with learning difficulties working under the guidance of charitable organisations, those with substance misuse disorders and those held within the criminal justice system.

Dubuffet and more recently scholar Poling, have argued the restrictions medicalisation place on outsider artists’ creativity to be removed, freeing the “works from any association with psychopathology and to recognise them instead as examples of uncompromisingly individual forms of creativity”. It is these impacts of institutionalisation that are of key concern for this research, and how this presents itself architecturally within the buildings, spaces and worlds of the sanitariums and psychiatric institutions up to this day. What impact does carceral architecture have on creativity? Is this a way we can pinpoint the presence of law within art? Another obvious presence, and well trodden ground in terms of theorisation, would be the prison. It is undoubtedly a clear mechanism of architectural institutionalisation and the progenitor of norms, the panopticon as the well versed example by Foucault who sees these carvel and care facilities as technologies of control.

This cannot be denied, and so perhaps the next question is, how did the architecture of the asylum make space for this generative art form?

how did the architecture of the asylum make space for this generative art form?

It is only since the Mental Health Act 1983 that those who had been committed to asylums had no right to appeal their certification, and given the increased interest in outsider art as a saleable genre within the art world, these legal implications are of concern as artists’ works are being sold and exhibited with questions of consent and intellectual property to be considered.

One prescient example is ‘John the Painter’ who was housed within a psychiatric hospital in Ireland and started to paint and daub all over his sheets and walls. His art work was noticed and exhibited at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in 2003, however, none of his paintings were attributed due to a Ward of Court. It is very often those marginalised by race, gender, disability, disempowered economically and politically, who fall within the brackets of outsider artists. A troubling history of outsider art is that it was often connoted with ‘primitivism’, and Non-Western art, which as a result problematically assimilates indigenous art, art of Africa, Asia, South America or Australasia as automatically ‘Other’.

Looking to Esther Leslie’s work on aesthetic forms through mineral and mechanical infrastructures, might be a way to start to unravel the connection between infrastructure and aesthetic norm (which we can also say is law) (Synthetic Worlds Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry, 2005). Amanda Beech is also an artist who has concerned herself with institutions, such as in ‘The Church, The Bank, ‘The Art Gallery’ (2012) whose work detects these connections between institutional and aesthetic forms.

Outsider Art/Outsider Law

This is part of broader research and book project ‘Outsider Art/Outsider Law’, that aims to understand the role of law in the creation of the term and genre ‘outsider art’, broadly art made by those without a traditional art school training, commonly with mental health difficulties. It investigates the development of English and Welsh mental health law, within the inception of outsider art, using legislative, discursive, artefactual and historical analysis to track its emergence within the institutional context. The research aims to understand the role of British psychiatric establishments in the creation of outsider art as a genre, as well as the use of the term ‘outsider’ itself and what it means to the artists concerned. The research seeks to practically support the protection of outsider artists regarding issues of consent and copyright when their works are bought and sold on the global art market, the research underpinning setting up an ‘Outsider Law’ clinic.

Dr Lucy Finchett-Maddock is Associate Professor of Law, Bangor University. She is currently working on the relationship between addiction and law, legal voids, law and vibration, the role of law in the development of outsider art and legal storytelling.

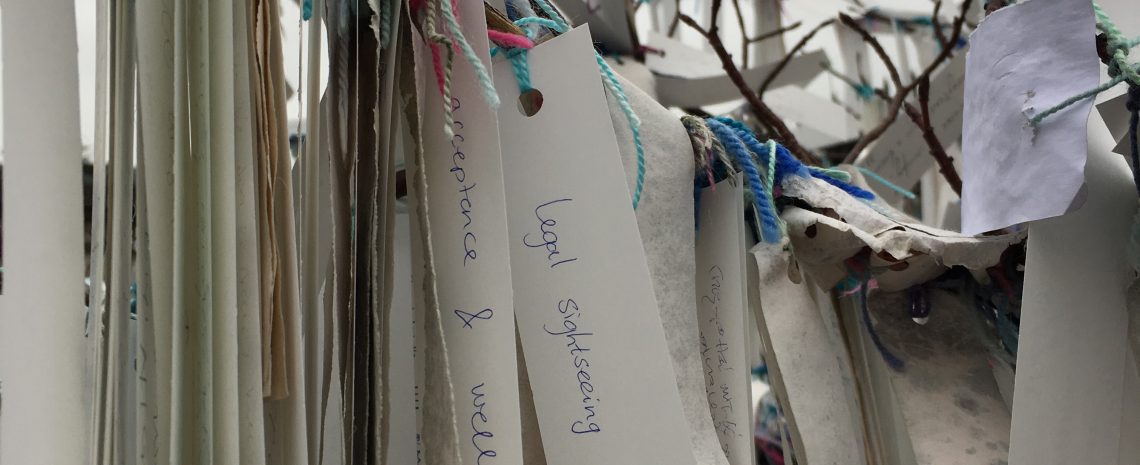

This piece is part of the legal sightseeing

mini-blog series on institutional architecture:

view the whole series!